$30,204 a Kilo: What the World’s Most Expensive Coffee Really Tells Us

Panama Geisha, Western Gatekeeping, and Dubai’s Expensive Performance of Belonging

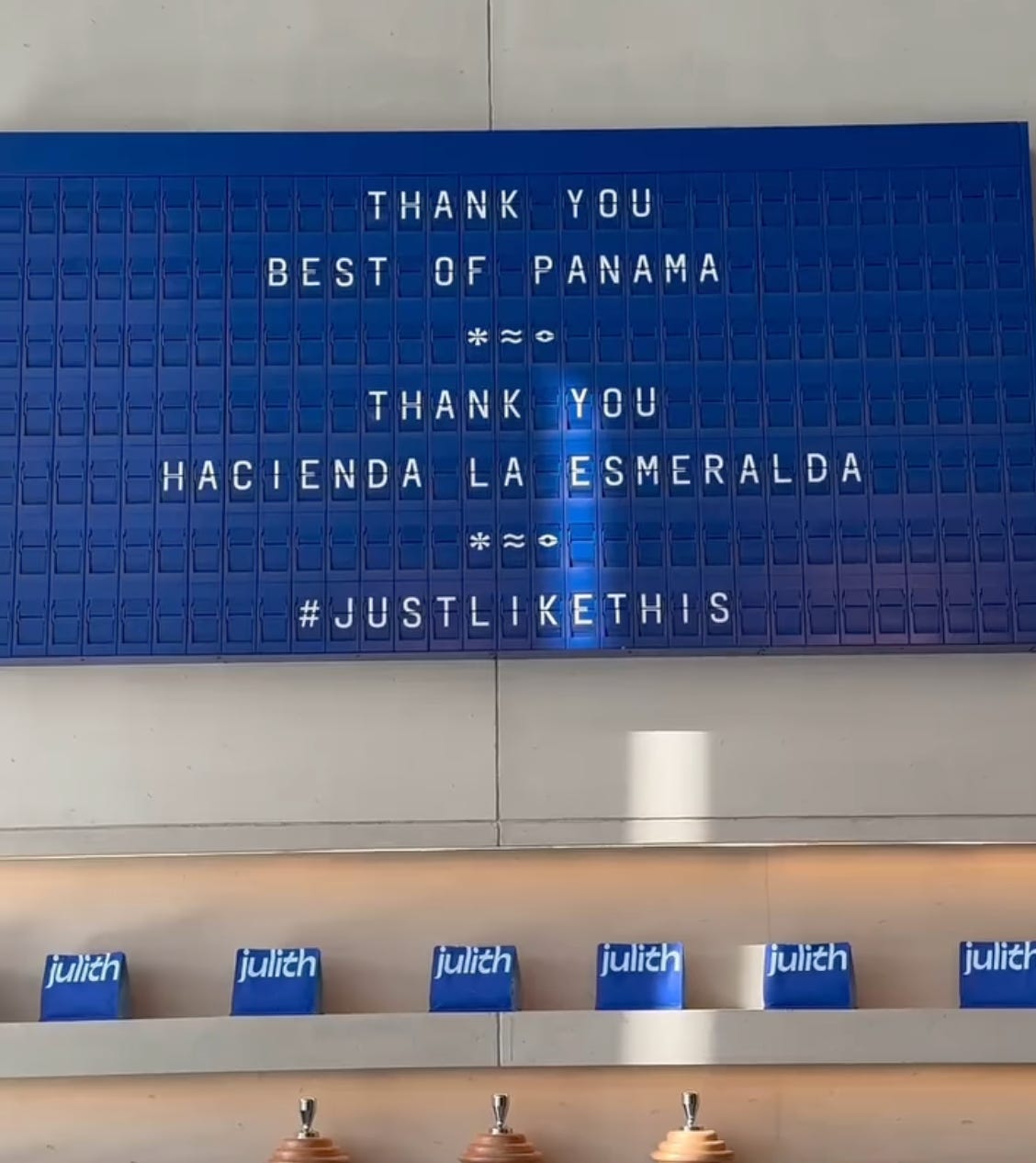

This week, the Best of Panama auction set a new record.

$30,204 for a single kilogram of coffee.

The buyer, Julith Coffee in Dubai, paid US $604,080 for a 20-kilo lot from Hacienda La Esmerelda — a washed Geisha scoring 98/100, the highest in the category’s history.

The specialty coffee world erupted in applause. The headlines declared it a victory for quality, a testament to the craft, proof that excellence will be rewarded.

But look closer, and it’s something else entirely: a mirror reflecting the West’s old habit of turning cultural gatekeeping into moral virtue — and the Gulf’s eagerness to buy a seat at that table, no matter the cost.

The Geisha Origin Myth

Let’s start with the obvious. Geisha didn’t start in Panama. It comes from the Gesha region of Ethiopia, collected in the 1930s and moved through research stations in East Africa and Costa Rica before being planted in Panama in the 1960s for disease resistance.

The name we use today — “Geisha” — seems less like an innocent typo and more like a willful mis-transcription of “Gesha,” the Ethiopian region where the variety was first collected. It has nothing to do with Japan’s geisha tradition, but that accidental overlap handed marketers a gift: a ready-made image of elegance and exoticism. In Western coffee circles, it became the perfect symbol: erased Ethiopian heritage wrapped in Japanese refinement, reframed through Panama’s misty highlands.

Then, in 2004, Hacienda La Esmerelda, an American-owned farm in Boquete, entered a separated lot of Geisha in the Best of Panama. It stunned the judges, broke price records, and rewrote the market’s hierarchy overnight. Suddenly, Geisha became the pinnacle of coffee.

Not because Ethiopia had lacked great coffee, but because the right people in the right place had finally declared it so.

Who Gets to Declare “The Best”

The estates that dominate the Best of Panama stage love to tell origin stories about vision, risk, and grit: the retired banker who bought a cattle farm in the ’60s and whose scientist son “discovered” a variety that would change coffee forever; the American family who arrived in the late 2000s to carve an ultra-high-elevation farm from the jungle, solar panels gleaming, consultants on call; the Swiss, Swedish, and elite Panamanian families who transformed their land into competition-winning machines.

These stories are true, but incomplete. What came before the work was just as decisive: the wealth to acquire prime land, the time to wait years for a return, the fluency to speak to international juries, the networks to place coffee on the auction block where the world’s most influential buyers sit.

You could almost admire it. Specialty coffee built an entire architecture to distinguish itself from the commodity trade: its own vocabulary of ethics, transparency, and merit. It presents itself as a level playing field, where the cup alone decides the price.

But even at its most idealistic, it can’t help itself. The stage is pre-built, the guest list fixed. “Anyone” can win — provided they arrive with the land, the money, the networks, and the cultural fluency to perform within a system designed by those already holding the microphone.

What seem to start as sincere ideals become irresistible marketing stories — and, in the right hands, massive payouts. The way Blue Bottle once positioned itself as the anti-Starbucks, only to sell a majority stake to Nestlé, is proof enough. Even in coffee, values have a price tag.

Meanwhile, Indigenous and Afro-Panamanian communities — whose labor is the bedrock of these estates — rarely own the land they work. They aren’t the names on the auction lots. They aren’t the ones feted in Melbourne or Boston. They are told, implicitly, that meritocracy exists here, but only if they can buy a ticket to the room — a ticket sold by the very people already inside.

When I think about my own ambitions as a roaster, I have to admit: if someone handed me that ticket tomorrow, I would be tempted to take it. But that is exactly how the system keeps going. Not by forcing us to play, but by making a prize so desirable that even its critics, given the chance, would find themselves on the stage.

Dubai Buys the Story

Julith Coffee opened on August 1, 2025, in Al Quoz, Dubai: a roastery, brew lounge, and concept store led by Turkish barista champion Serkan Sağsöz. It is, without question, beautiful — high ceilings, surgical lighting, packaging that could sit beside Chanel without flinching. Everything about it says this is what world-class coffee looks like.

But some design serves to distract, using beauty as a kind of laundering — until the only provenance that matters is the brand itself.. And here, the story begins not in a farm or a roasting drum, but in a ledger. Just a week after opening, Julith’s first act on the global stage wasn’t a roast, a menu, or a competition win, but a receipt: over half a million dollars for the most prestigious lot at the most prestigious auction, anointed by the world’s most influential palates.

Sağsöz’s championship is real, but championships don’t bankroll spaces like this. So who owns this stage? We can guess.

In the Gulf, prestige often comes from alignment with Western luxury: watches, handbags, rare Bordeaux — and now, auction coffee. If the West says this is the best, buying it at the highest possible price is the quickest way to be seen as part of that world.

It’s a perfect symbiosis: the West reaffirms itself as arbiter of taste and value; the Gulf purchases a seat at the table. Both sides leave satisfied. And for half a million dollars, you don’t just buy coffee — you buy the right to tell someone else’s story as if it were your own.

A $30,204 Mirror

Yes, Lot GW-01 is probably exquisite coffee. But this auction isn’t a victory for coffee — it’s a victory for the small circle that defines what “victory” means. It’s a piece of theater in which the West’s self-image as an ethical tastemaker and the Gulf’s desire for Western validation meet in perfect harmony, underwritten by a sum of money that will do nothing to shift who gets to win next year, or the year after that.

The West talks about equity while keeping the gates locked. The Gulf talks about arrival while buying a place in someone else’s story. And everyone else — the farmers without capital, the communities without land titles, the countries whose varieties are “discovered” only when they pass through Western hands — stays exactly where they’ve always been.

I do not consider myself immune to these stories. A part of me is drawn to them. If my own work found its way into these rarefied circles, I might feel the pull of their logic — the idea that a higher score, a higher price, is proof that we’ve made it. But to what end? A buy-out? A personal empire?

And this, my friends, is how the colonizer mindset endures: not only by rewarding the few who built it, but by quietly recruiting the rest of us to aspire to it.